Intraarticular injections in horses are beneficial for managing various musculoskeletal conditions, but they do come with associated risks and should be performed by a suitably qualified and experienced veterinarian. Furthermore, owners should be well-informed about the procedure, potential risks, and benefits before making the decision to go ahead.

Here are some key points to consider;

Benefits:

The three most common reasons for a vet to perform a joint injection are:

- To anaesthetise or “block” a joint during lameness evaluation.

- To medicate a joint in the treatment of joint pain or osteoarthritis.

- To sample the fluid from a joint when there is a suspicion of infection.

Risks:

Owners should be made aware of the potential risks associated with intraarticular injections, which may include infection, joint damage, or adverse reactions to the medication itself. Joint infections can be difficult to treat, especially if they are associated with the use of corticosteroids which have the capacity to mask clinical signs of joint infection for several days. Long term use of corticosteroids can also result in cartilage breakdown (“steroid arthropathy”) and have significant side effects such as contributing to the onset of laminitis, or other systemic effects. The risk of adverse events should always be weighed against the potential benefits regardless of the medication used.

Procedure Details:

Before injection, surgical preparation of the injection site is essential.1 This may include clipping the site. The area is scrubbed with antiseptic wash and then wiped or sprayed with surgical spirit. Restraint depends on the site and the nature of the horse, and oftentimes mild sedation is used, unless doing a lameness exam.

Recovery and Rehabilitation:

Expected recovery times and any post-injection care or rehabilitation that may be required, such as rest, exercise restrictions, or physical therapy vary depending on the specifics of each case. With 2.5% iPAAG, 48 to 72 hours rest is recommended before commencing a graduated rehabilitation plan with the horse expected to become lame free 2 to 4 weeks after treatment.2

Adverse Reactions or ‘Joint Flares’

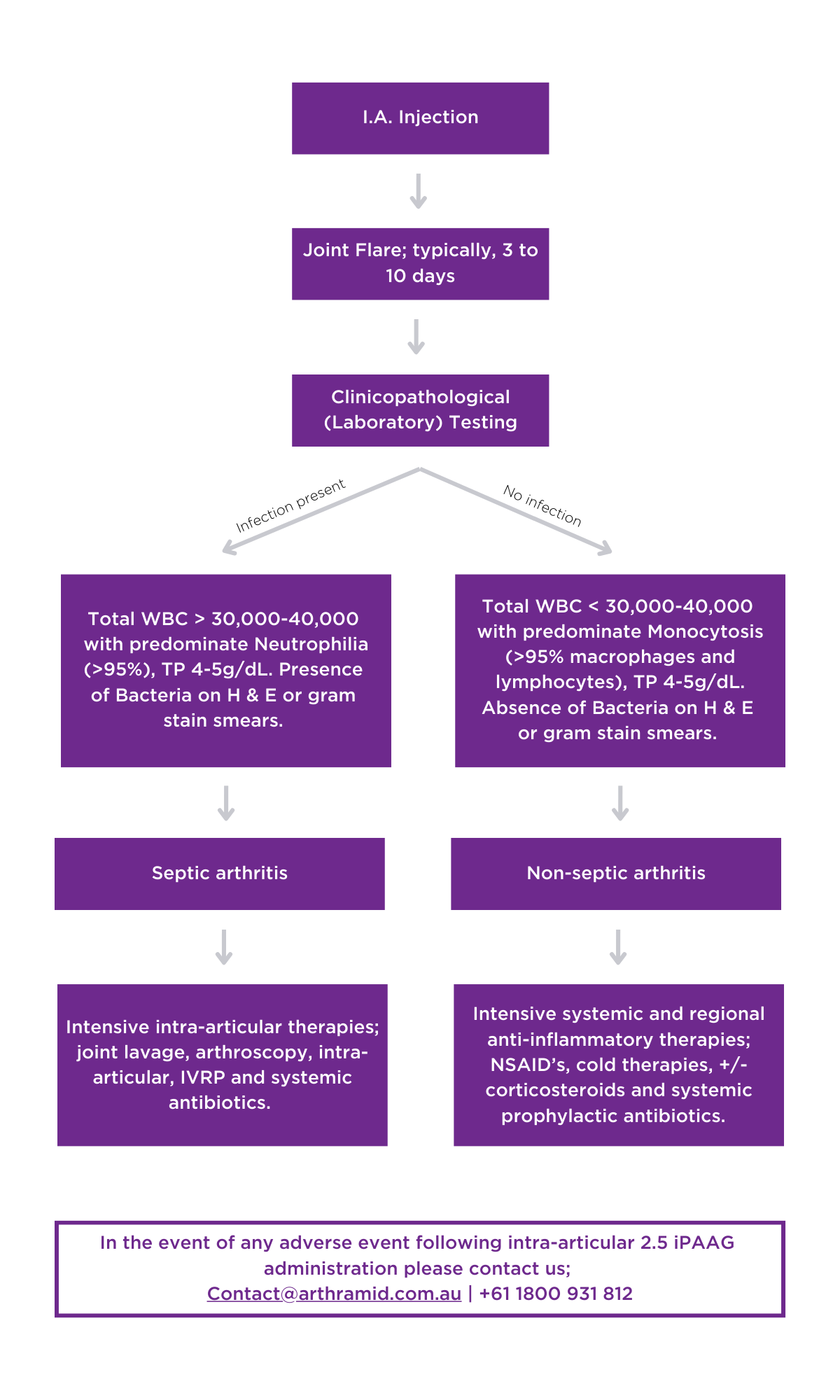

As with any drug administered, there is always a chance that the horse’s immune system will respond inappropriately to it. Types of adverse reactions vary but when they happen in joints, they commonly result in similar signs to infection; with heat, swelling, pain and lameness. This adverse reaction is referred to as a “flare” and unlike infection does not involve bacteria (i.e., it is sterile). It is important to distinguish between joint infection and a flare (by sampling the synovial fluid) because treatment differs between the two. In most cases horses that have a synovial flare are treated with rest and anti-inflammatories, although in severe cases lavage of the joint might be required.

Considerations in the unlikely event of an adverse reaction (‘Joint Flare’) with 2.5% iPAAG

Based on available published studies and combined clinical experience the complication rate for intra-articular injections with 2.5% iPAAG is extremely low (estimated at 0.04% or less than 1 in 2,500). 3 Complication rates with other joint treatments are reported at 7.8 cases/ 10,000 injections, which is equivalent to one in 1,282 joint injections, and can be as high as 0.5% to 0.7%.4

2.5% iPAAG induces a typical foreign body response5, which is actually how it works. Within 1-2 weeks, some animals can develop transient pain and oedema at the treatment site. If not caused by infection, these reactions are typically self-limiting and will resolve within a few days. But in severe cases it is important that infection is ruled out as a possible diagnosis as this requires a different treatment strategy.

Laboratory testing should be performed prior to starting any intra-articular treatments to exclude infection (sepsis).6 The absence of bacteria and a monocytosis rather than a neutrophilia seen on cytology determines these cases should be treated as an ‘non-septic inflammatory reaction’ with intensive anti-inflammatory therapy (systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, cold therapy, +/- corticosteroids) rather than aggressive surgical or intra-articular interventions (arthroscopic debridement, joint lavage, or intra-articular antibiotics) that may in fact exacerbate the already exuberant immune response occurring inside the joint in any ‘flare’ response.

Aminoglycocide antibiotics

Gentamycin and Amikacin are commonly employed in the treatment of joint infections. These are known to be cytotoxic and can even be detrimental to the joint environment, inducing inflammation and even cartilage degradation.7 Decisions on their use, especially in cases with a history of 2.5% iPAAG administration and prior to laboratory results to confirm sepsis, should be carefully measured as they may in fact contribute more harm than previously considered. Safety and pharmacokinetics of alternative antibiotic choices have been investigated and include ceftiofur, vancomycin, enrofloxacin, and marbofloxacin.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are potent antiinflammatory drugs and their use may be warranted in severe cases and where sepsis is excluded. The use of a single systemic dose of corticosteroids (50mg dexamethasone) or via regional limb perfusion ((10 mg dexamethasone-in a 20 ml volume- repeated q.24 hours for 3 to 5 days) may be considered useful in severe ongoing cases to help suppress the adverse inflammatory response to the gel.

Patient management

The patient should be rested, and further adjunctive therapies can include cold bandaging, cold hosing, and topical NSAID’s. Joint lavage should only be considered in severe acute cases (<7 days) where the benefits of removing any non-integrated gel potentially outweighs the risks of contributing to the ongoing non-septic reaction active in the joint. [It is known that by 10 days the gel is fully integrated within the sub-intima of the joint capsule with a synovial cell layer again forming over the top3]. Veterinarians may consider the prophylactic use of systemic antibiotics, and should discuss with the owner that a response to treatment may take up to 2 weeks to occur.

When to treat with 2.5% iPAAG

Due to Arthramid Vets’ unique mode of action it is prudent to consider treating the animal during periods of reduced exercise demands or earlier in the animals training programme than what is normally considered with conventional treatments.

In the event of infection then normal veterinary treatment regimens for intra-articular sepsis are indicated. It is important to understand that 2.5% iPAAG does not interfere with antibiotic penetration nor does it sequestrate bacteria. Less is known about the performance or safety of other PAAG products, and the widespread and largely indiscriminate use of these products in some countries has caused serious long-term complications, mainly infection and granulomatous reactions.8

Conclusion

The idea of a treatment such as 2.5% iPAAG that acts as a bio-scaffold and through its presence aids the body’s natural responses to injury or disease represents a paradigm shift in our thinking about the treatment of osteoarthritis.

With any drug administered intraarticularly, there is always a risk that the horse’s immune system may respond inappropriately to it. The key is a shift in our understanding to influence how we use this product and to manage any ‘flare’ reaction to it differently to what we have traditionally done in these types of cases.

References:

- Mitchell C. “Aseptic Technique”. In Costa LRR and Paradis MR, editors. Manual of Clinical Procedures in the Horse. M.R. Wiley Blackwell; 2018; 123-125.

- de Clifford LT, Lowe JN, McKellar CD, McGowan C, David F. A Double-Blinded Positive Control Study Comparing the Relative Efficacy of 2.5% Polyacrylamide Hydrogel (PAAG) Against Triamcinolone Acetonide (TA) And Sodium Hyaluronate (HA) in the Management of Middle Carpal Joint Lameness in Racing Thoroughbreds. J Equine Vet Sci. 2021; Dec;107:103780. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2021.103780. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 34802625.

- Tnibar A. Intra-articular 2.5% polyacrylamide hydrogel, a new concept in the medication of equine osteoarthritis: A review. J Equine Vet Sci. 2022; 119: 104143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2022.104143.

- Van Weeren PR. Septic Arthritis. In: McIlwraith CW, Trotter GW, editors. Joint Disease in the Horse. Philadelphia: Saunders WB; 1996. p. 91-104

- Anderson, J M, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Immunol. 2008; 20(2): 86-100. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.smim.2007.11.004.

- Rinnovati R, Butina BB, Lanci A, Mariella J. Diagnosis, Treatment, Surgical Management, and Outcome of Septic Arthritis of Tarsocrural Joint in 16 Foals. J Equine Vet Sci. 2018; 67: 128-132. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2018.04.003.

- Pezzanite L, Chow L, Hendrickson D, Gustafson D, Russell M, Stoneback J, Griffenhagen G, Piquini G, Phillips J, Lunghofer P, Dow S, Goodrich L. Evaluation of Intra-Articular Amikacin Administration in an Equine Non-inflammatory Joint Model to Identify Effective Bactericidal Concentrations While Minimizing Cytotoxicity. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2021; 8. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.676774.

- Narins RS, Schmidt R. Polyacrylamide hydrogel differences: Getting rid of the confusion. Drugs Dermatol. 2011; 10 (12): 1370-1375.